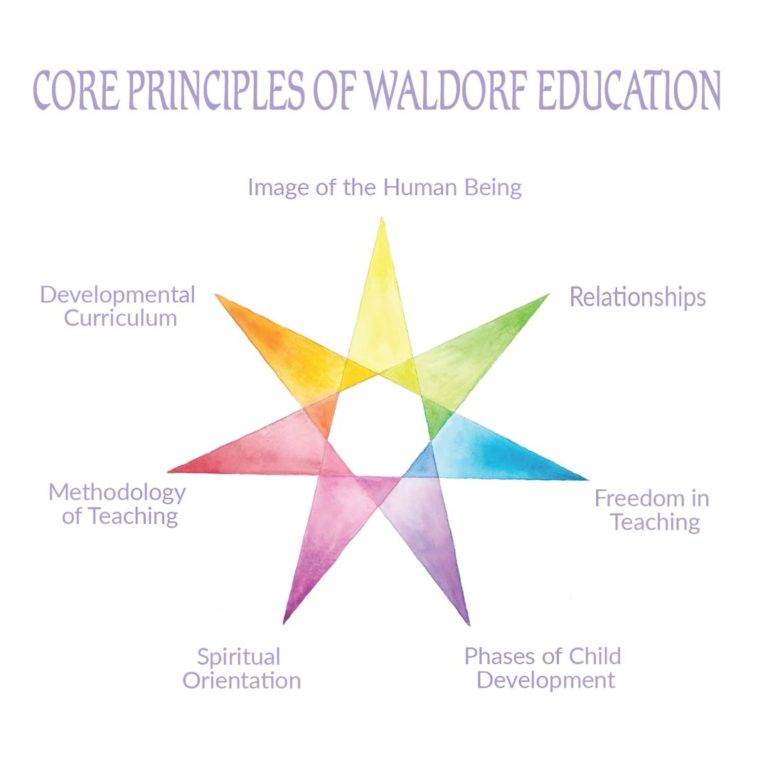

core principles of waldorf education

Waldorf education can be characterized as having seven core principles. Each one of them can be the subject of a life-long study.

The Pedagogical Section Council of North America (PSC) crafted the original Core Principles document in the early 2010s, and wrote a series of articles in support of studying it that were later published, with additional contributions, in the book The Seven Core Principles of Waldorf Education. The document was never meant to become fixed for all times, however, and the PSC felt that, almost ten years on, it was time to revisit and update it.

Of particular note is the fact that both AWSNA and the Alliance for Public Waldorf Education took the original Core Principles and created variations of their own for their institutional needs. The existence of three different sets of principles has caused some confusion. This set of Core Principles is expressly meant as a tool for practicing teachers rather than for institutions.

1. Image of the Human Being: The human being is an organic being of Spirit, soul, and body, meaning that changes in any one part will be reflected in the whole. During three distinct periods of development from birth to twenty-one, the Spirit/soul gradually takes hold of its physical bodily instrument. In this sense, the physical body is the material precipitate, rather than the origin, of spiritual development. As the irreducible spiritual individuality within each one of us, the Self pursues its journey through successive incarnations. Its immortality extends equally in both past and future directions.

2. Phases of Child Development: The child develops in an archetypal sequence of approximately seven-year phases. Each phase has unique and characteristic physical, emotional, and cognitive aspects. As children develop through these phases, each one unfolds the archetype of human experience in a unique manner. Understanding the seven-year-phases is a foundation for teachers working in early childhood, elementary grades, and high school.

3. Developmental Curriculum: The Waldorf curriculum is created to meet and support the different phases of child development. From birth to age 7, the child’s need is to imitate the surrounding world. From 7 to 14, the foremost principle is that of following the teacher’s warm and insightful guidance. During the high school years, the development of independent judgment is exercised under the banner of idealism.

4. Freedom in Teaching: Rudolf Steiner gave indications for the development of a new pedagogical art, with the expectation that “the teacher must invent this art at every moment.” The teachers’ freedom to respond to the specific needs of the children they teach with authenticity and creative innovation arises from the weaving together of the following: ongoing research and insight into child development and the principles of Waldorf education, commitment to exploring current educational thinking, and ongoing collaboration with colleagues. This creative freedom is so essential to the educational process that interference with it by the school, by parents, by a standardized testing regimen, or by the government––while perhaps necessary in a specific circumstance (for safety or legal reasons, for example)––is nonetheless a compromise.A note about school governance: while not directly a pedagogical matter, school governance is an essential aspect of freedom in teaching. Just as a developmental curriculum should support the phases of child development, school governance should support the teachers’ pedagogical freedom (while maintaining the school’s responsibilities towards society).

5. Methodology of Teaching: A few key methodological practices guide the grade school and high school teachers. Early childhood teachers work with these practices appropriate to the way in which the child before the age of seven learns, out of imitation rather than direct instruction:

- Artistic metamorphosis: the teacher should understand, internalize, and then present the topic in an artistic form. Artistic does not necessarily mean practice of the traditional arts (singing, drawing, sculpting, etc.), but rather that, like those arts, the perceptually manifest reveals something invisible through utilizing perceptible media. Thus, a math problem or science project can be just as artistic as storytelling or painting.

- Teaching through image: by means of story, picture, and metaphor, the teacher helps students to develop the

- rather than just in abstract analytic concepts.

- From experience to concept: the direction of the learning process proceeds from the student’s soul activities of willing through feeling to thinking in a process of discovery. This mirrors the development of human cognition, which is at first active in the limbs and only later in the head. In the high school the context of the experience as a whole is sometimes provided at the outset.

- Holistic process: teaching proceeds from the whole to the parts and back again, addressing the whole human being.

- Archetype of health: teaching acts out of assumptions of health and the pursuit of the good, rather than of illness and the avoidance of evil or misfortune. In other words, teaching is salutogenic, not pathogenic, in outlook and intention.

- Use of rhythm and repetition.1 (See footnote below.)

- Educating, rather than instructing: the desired outcome of Waldorf education is the development of intellectual, emotional, and moral capacities, not simply the delivery or transmission of information and its applications.

6. Relationships: Human interactions constitute the heart of Waldorf education. The task of teachers at all levels is to support the developing individuality of each student and the social health of the class as a whole. Relationships are strengthened and deepened because they are cultivated over many years in face-to-face interactions that electronic means cannot replace. In addition, teachers are committed to healthy working relationships with their colleagues and with the parents of the children in their classes. Cultivating these relationships enhances the social life of the school community and further enriches social-emotional learning for the students.

7. Spiritual Orientation:In order to cultivate the Imaginations, Inspirations, and Intuitions needed for their work, Rudolf Steiner gave the teachers an abundance of guidance for developing an inner, meditative life. This guidance includes individual professional meditations and an imagination of the circle of teachers forming an organ of spiritual perception. With the help of these practices, teachers can be confident they are “not alone” with their students in the classroom. Meditative life also constitutes a form of self-care that is crucial for professional vitality. Faculty and individual study, artistic activity, and research form additional aspects of ongoing professional and spiritual development.

_______________________

[i] There are four basic temporal rhythms with which the Waldorf teacher works. The most evident of these is the day-night (or two-day) rhythm. Material that is presented on a given day is allowed to “go to sleep” before it is reviewed and brought to conceptual clarity on the following day. A second rhythm is that of the week. It is “the interest rhythm” and teachers strive to complete a topic within a week of engaging it. A paper returned to the student after more than a week will no longer interest the student. The only interesting thing will be the teacher’s comments, but the topic itself will already have flown out the “interest window.” A third rhythm is that of a month (or four weeks). A block, or unit of instruction, is usually best covered in four-week periods. This life-rhythm, which can be understood, for example, in contemplating feminine reproductive cycles, brings a topic to a temporary level of maturity. The last of the pedagogical rhythms is that of a year. This is the time it may take for a new concept to be mastered to the degree that it can be used as a capacity. Thus, a mathematical concept introduced early in third grade should be mastered sufficiently to be available as a capacity for work by the beginning of fourth grade.